Continental Connections, Berlin, 17th–18th October 2022

This hybrid conference was organized by the Netherlands and German indexing networks (NIN and DNI) and the Society of Indexers, in cooperation with the German Society for Information and Knowledge (DGI). The conference took place in Berlin. I attended as an online delegate.

There were two stand-out themes of the conference:

1. Non-linear texts and reading styles

2. Translations of indexing terminology and indexes

1. Non-linear texts and reading styles

The first speaker to outline this theme was Professor Urs Stäheli, who spoke about the politics of lists. He used indexes as an example of professional, institutionalized list-making. He described the process of creating an index as conversion from analogue (continuous) to digital (discontinuous) format; the linear narrative “analogue” text is “digitized” and reordered into the index list at the back-of-the-book. He discussed the potential implications of the choices that are made during this process.

Similar themes were covered by the next speaker, Professor Kiene Brillenburg Wurth. She showed how texts developed from narrative, linear forms (oral storytelling and scrolls) to tabular forms when printing was developed from 15th Century onwards. Gradually, writing has become increasingly visual and spatial. Many stages of innovation have occurred as books developed to include more and more common references points and aids to the reader such as page numbers, tables of contents, chapters, headings, summaries and indexes. This “tabularlity,” or spatial arrangement of the information on the page, has facilitated faster access to information and enabled “readerly activism” by giving the reader the ability to choose their access points within a text. The temporal element, the narrative process of telling a story through time, is replaced by the spatial element, with texts becoming places to visit and return to. The digital age brings more questions about who or what will read, as machine-reading and artificial intelligence is developed.

On the second day of the conference, Judith Flanders spoke on her book A Place for Everything: the Curious History of Alphabetical Order. In her book she compares the reading of narrative prose to other types of reading (browsing, checking endnotes, reading maps, consulting timetables), and writes:

much of our reading, therefore, is not remotely narrative, not destinational, but instead is directed towards retrieving a single piece of information, which is often found by searching a list that is ordered alphabetically

– Judith Flanders, A Place for Everything, xxv

She describes how hierarchical sorting was once the “natural impulse” (xix) but then shows how alphabetical sorting is the only type of sorting which does not require previous knowledge of the system beyond knowledge of the order of the letter symbols. It is also valued for its neutrality. She quotes the compiler of the first French bibliography in 1584 who used alphabetical order to avoid offending anyone within a hierarchical structure.

sorting is, ultimately, magical…this magical tool, the alphabet, bestows the ability to create order out of centuries of thought…to locate the information we need, and disseminate it in turn

– Judith Flanders, A Place for Everything, xxiii

2. Translations of indexes and indexing terminology

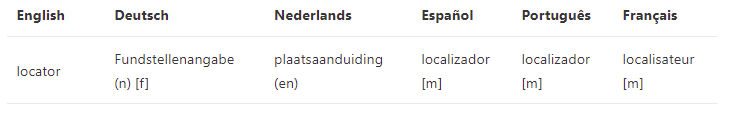

Jochen Fassbender and JoAnne Burek introduced the International Indexing Dictionary now available online. A group of multilingual indexers began the process of compiling it after meeting at the Indexing Society of Canada/Société canadienne d’indexation (ISC/SCI) online conference in 2021. The dictionary currently lists indexing terms in six languages: English, French, German, Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese.

Jochen used a metaphor about martial arts training. Martial arts techniques are learned by heart and by name, and Jochen suggested that indexing techniques should be learned in the same way, by heart and by name, to help raise awareness of the techniques available to us. It was interesting to hear about the lack of translations between languages for terms that are used frequently in others; examples from English include “forced sort” and “back of the book”. This leads us to think about how and why indexing practices developed differently in different countries.

The translation theme continued with Paula Clarke Bain and Dennis Duncan, who spoke about the Italian and German translations of Index, a history of the. Often when books are translated, they are re-indexed in the new language. However, Paula’s index to Dennis’ book was so integral to the text, with the inclusion of many indexing techniques and jokes, that the decision was made to translate it. Many difficulties had to be overcome, including, acrostics, anagrams and word chains that needed to work in the translated language. For example, the English edition includes the entry “X, no entries beginning with” but this could not be included in the Italian edition because “xilografie” was included (“woodcuts” in English).

The conference also included sessions on indexing in China, E-book indexing, embedded indexing, communication and marketing, an overview of the current developments in publishing, and a publishers’ panel. It was a full, varied and useful programme.